Sensors and gauges - Observability in distributed systems

Imagine a world where a pilot would have to fly an over 500-ton, 4-engined Airbus A380 with virtually no flight instruments, only a primitive joystick and maybe a headlight for night landings. Imagine a captain navigating through a coral reef full of underwater ridges, or maneuvering beneath the polar ice sheet, all while commanding a submarine without sonar and basic instruments. Imagine a construction equipment operator required to excavate a 400m long, 3m deep ditch - although the excavator they are manning only has a number of peepholes in solid metal cabin walls instead of proper windows.

Does any of this sound like an impossible, if not suicidal mission to you? Now, imagine we are talking not about a single airplane, a single submarine or a single piece of construction equipment - but rather a myriad of them. Tens, if not hundreds of individual airplanes, submarines and excavators working towards a common goal; All the while struggling to maintain situational awareness and get the job done without crashing into each other, or into the ground, and ideally without any collateral damage.

At this point, it might appear unimaginable, and rightly so. Unfortunately, this is more or less the reality of working with a distributed system lacking observability measures at all, or equipped with inadequate instruments. In this post, we will explore how distributed systems are commonly monitored, and how various parts of observability stack help Engineering Teams maintain situational awareness.

What is observability?

According to OpenTelemetry, observability means an ability to gain insights about the state of a system without having to know its internal structure and details, or to analyze its internal states. In other words, any data deliberately emitted by a system could be considered part of instrumentation enabling observability, when:

- It contributes to a better understanding of how the system functions,

- The data can be accessed and processed with the purpose of analyzing the state of a system,

- It enables troubleshooting of a live system, even in case of newly encountered problems.

The data, or signals, emitted by an instrumented system are typically divided into three distinct categories:

- Logs,

- Metrics,

- Traces.

Logs

Logs are text-based signals correlated with a timestamp at which they were emitted. They are primarily intended to be read by a human, either in raw form or after additional processing. Logs are typically written to two destinations:

- Dedicated log files,

- Standard output -

stdoutand sometimesstderr.

Unstructured logs

In their simplest, unstructured form, logs can be as simple as a Unix or ISO timestamp and text message:

[2024-10-26T09:11:34.000Z] Application starting...

[2024-10-26T09:11:34.042Z] Loading module A...

[2024-10-26T09:11:34.157Z] Module A loaded.

[2024-10-26T09:11:34.198Z] Loading module B...

[2024-10-26T09:11:34.411Z] Error: Encountered problem when loading module B: "file libfizzbuzz.so not found".

[2024-10-26T09:11:34.493Z] Error: Application failed to start.

This format is reasonably readable for a human, rudimentary search can be done against it e.g. with grep, and it generally suffices when running a single program. However, it bears very little context, depending entirely on the quality of individual log lines, and bearing no additional information. These traits could make it problematic when more sophisticated processing is required, especially when multiple threads, processes or programs are running and emitting some logs, which might be related to each other. Comparing multiple unrelated log files on a single host is unwieldy enough, and doing so in a distributed system is just as frustrating as it is impractical.

Structured logs

Due to limitations of unstructured logs, it is far more useful to use a certain log formatting approach that includes additional context to the log messages, and to enforce a certain way this context is structured for easier processing. A frequently used, though not exclusive log format is JSON log, where each individual line is a valid JSON object:

{ "timestamp": "2024-10-26T09:11:34.000Z", "msg": "Application starting", "level": "INFO", pid: "1253", "threadId": "main" }

{ "timestamp": "2024-10-26T09:11:34.042Z", "msg": "Loading module A", "level": "INFO", pid: "1253", "threadId": "main" }

{ "timestamp": "2024-10-26T09:11:34.157Z", "msg": "Module A loaded", "level": "INFO", pid: "1253", "threadId": "main" }

{ "timestamp": "2024-10-26T09:11:34.198Z", "msg": "Loading module B", "level": "INFO", pid: "1253", "threadId": "main" }

{ "timestamp": "2024-10-26T09:11:34.411Z", "msg": "Encountered problem when loading module B: \"file libfizzbuzz.so not found\"", "level": "ERROR", pid: "1253", "threadId": "main" }

{ "timestamp": "2024-10-26T09:11:34.493Z", "msg": "Application failed to start", "level": "INFO", pid: "ERROR", "threadId": "main" }

While it is far less readable for humans in a raw form, it makes bulk processing of logs, log analysis and correlation far easier - compared to unstructured logs. Enforcing a particular, consistent format makes parsing much easier, meaning that contextual information can be extracted programmatically with minimal risk of errors and mistakes. For readability, it is not uncommon for distributed system components to have two modes of logging:

- Unstructured logs, used in local development to troubleshoot the component ad-hoc while running it on a local device, and typically disabled upon deployment,

- Structured logs, to be collected and processed by dedicated log processing and analysis tools, such as Splunk or Logstash when application is deployed to environments.

Log context

Apart from context generated by the application itself, logs can be further enhanced throughout the process of collecting them and feeding into log processing tool, such as collection of logs:

- From relevant applications running on a certain host, containers running in a Kubernetes pod etc.

- From a set of hosts, e.g. belonging to a single subnet, Kubernetes namespace or cluster etc.

- When aggregated logs from multiple sources are fed into the log processing solution, and can be labeled as originating from a single environment.

While log contexts may include just about any items imaginable, in virtually any format, some of the most commonly encountered context items in distributed systems include:

- Timestamp (according to system clock),

- Location from which the log was emitted, such as Java class name,

- Trace ID, correlating various log entries across any applications related to a single execution, such as triggered by a request or event,

- Request ID, which is often found in systems utilizing request-based communication internally or externally,

- Event ID, in case of event-triggered actions,

- Span ID and parent Span ID, positioning log in the context of execution tree,

- Other traceability metadata,

- Log level, to distinguish informational, debugging, warning, error and other logs by their importance,

- Application name / identifier,

- Request URL,

- Hostname,

- IP address,

- Container ID - in case of containerized applications,

- In case of Kubernetes, labels such as workload resource name, namespace and cluster,

- Certain HTTP headers, such as user agent,

- Outcomes, such as statuses.

Such additional log context allows to perform basic log filtering, log aggregation, and more advanced analytical queries. It is possible to compute metrics from logs, and to use logs with rich traceability context with analytical queries as a substitute for separate distributed traces collection. However, replacing dedicated metrics and traces with log analytics tends to be compute intensive, and for larger log volumes is often slow.

What makes logs meaningful?

As the primary use of logs is troubleshooting and analyzing the systems during and after an incident, and sometimes also capturing anomalous behaviors, there is a number of factors improving the experience of log analysis:

- Whether it is possible to read or infer relevant circumstances, leading to emitting this log line,

- Ability to find out cause-effect relationships between log entries originating from various sources,

- Consistency of log format and context, for instance presence of frequently used context metadata across the system under the same key,

- Conciseness of log entries, allowing to understand the circumstances more easily without the need to get through a wall of text,

- Structuring relevant context, including context exclusive to particular application or application layer,

- Each log should be created with a purpose, such as logging on side-effects and as milestones / checkpoints for more complex processes, as opposed to logging on every function call,

- Frequency of logs decreases with increasing log level:

- Debug traces are typically used when running the application locally and/or in tests, and are by far the most frequently emitted, granularity is often desirable,

- Info logs should mark key operations such as side-effects and milestones, typically on a happy path,

- Warn logs are frequently used to indicate anomalous and possibly undesired behaviors, which are not considered failures - though might require attention, especially if the frequency spikes,

- Error logs are often reserved for outright failures, unexpected errors such as the unavailability of an upstream service or failure to connect to a database - indicating attention is required.

There are a few practical symptoms that might indicate a need to revisit application logging:

- Software and Support Engineers deliberately filtering out unwanted log entries when troubleshooting,

- Inability to correlate logs across applications, or even within a single application,

- Relying heavily on log queries that perform log message transforms to extract useful context - indicating that the actual context included in log entries might be insufficient,

- Inappropriate logs levels, either too high or too low compared to actual severity of an event causing this log to be emitted,

- Inconsistency of log context, leading to some logs having certain high-importance context while others lack it, or keeping context under a different key - possibly due to a typo or inconsistent usage of letter case,

- It is important to include some error context to facilitate troubleshooting, however including long stack traces in their entirety may lead to cluttered logs or even break log processors, which might have limits on log line length,

- The log volume and/or log processing costs get out of hand, causing difficulties with facilitating log processing, or log processing bills that are beyond the organization’s budget.

Logging-related risks

Among logs, metrics and traces, logs are probably the most commonly found type of instrumentation. Not every system is instrumented with traces, and even metrics are not always there, however logging is nearly universal. It also tends to be the most flexible instrumentation, allowing Software Engineers to put just about any content in log messages at any time and spot in their codebase.

For these reasons, it is not uncommon for logging to become highly problematic, if not dangerous for the organizations. Examples of such situations include:

- Excessive logging of specific data points and accidental inclusion of sensitive metadata may lead to severe security risks - for instance, when Authorization headers or cookies appear in logs,

- In some cases, it is useful or even desirable to include additional context related to user interaction - such as some request parameters or other properties. However, logging such information liberally may lead to privacy and compliance issues in case e.g. PII data would be logged, or may needlessly disclose confidential customer data to unauthorized parties,

- Excessive logging might lead to loss of logs in case log ingest quotas have hard limits - if an incident occurs after a system hits such a limit, one of the crucial tools to investigate the incident is not available.

Logging good practices for distributed systems

There is a number of aspects deserving particular attention when instrumenting distributed systems with logs:

- Use structured logs across the entire system, with log format of choice - as long as it suits your log processing needs,

- Ensure log context is included in a consistent manner across the system - during incidents, nobody should end up scratching their head, and struggling to write a log search query that would find TraceId across 5 competing log structures in the system,

- Align on what context should be logged in given situations - handling HTTP requests, database or message queue interactions to name a few - and under what keys. This allows to process logs from various parts of a system in a consistent manner, and ensures one does not lose track of important information,

- Frequently processed log line contents are good candidates for inclusion in log context,

- Instead of logging in every single function of each application, prioritize critical points such as side effects and I/O to limit how much log lines individual components produce,

- Apply reasonable log levels when logging, and reserve higher log levels for events that indeed require the most attention,

- Ensure that log lines are concise and information-dense.

Metrics

Metrics describe a set of measurements and indicators, which are typically continuously exposed by an application at runtime. In a typical application instrumented with metrics, they are either pushed by application instrumentation to a metrics server/collector, or exposed via some API (oftentimes an HTTP endpoint) as a set of values annotated with metric name, type, and relevant labels or attributes. Due to their nature, metrics are primarily used to supply measurements of quantifiable characteristics of a component or system, which are then periodically collected and sent to a metrics server to be processed as time series.

Types of metrics

The three most basic, and frequently used kinds of metrics are:

- Counters - their values, with the exception of application restarts, are typically monotonic, and increment every time a certain event occurs within an application - such as receiving a request. On metrics server side, they are frequently converted to deltas between measurements, allowing to compute user-facing metrics such as rates of certain events - for instance, sending back certain HTTP status codes or encountering an error.

- Gauges - unlike counters, they are not monotonic and normally are not meant to be converted to deltas. Gauges are useful to measure certain values rather than observe events. Good examples of gauge usage is to observe CPU and memory utilization.

- Distributions - expose statistical data that cannot be easily expressed or processed as counters and gauges. Distribution metrics typically expose bucketed values, with buckets corresponding to certain percentiles, denoting the number of occurrences within the bucket, or below the bucket’s upper bound. This way, distribution metrics allow to gain useful statistical insights, such as distribution of request latency by HTTP endpoint. Examples of distributions include histogram and summary metrics.

Pull vs push semantics

Some metrics implementations, such as Prometheus, opt for pull semantics where metrics exporter only exposes the metrics. It is done in such a way that metrics collector pulls (or scrapes) the metrics from an exporter:

An alternative approach is push semantics, seen in StatsD and OpenTelemetry, where the metrics exporter is responsible for sending the metrics data over to metrics collector - or metrics server directly, if collector is omitted:

Metric data formats

Metrics come in a plethora of formats depending on metrics exporter and server, as well as pull and push semantics. Examples include:

Implementations of metrics data formats vary from plaintext, such as Prometheus, through text-based formats as in Graphite, to Protocol Buffer schemas seen in OpenTelemetry.

A Prometheus example showcases how metrics can be structured:

# HELP http_requests_total The total number of HTTP requests.

# TYPE http_requests_total counter

http_requests_total{method="post",code="200"} 1027 1395066363000

http_requests_total{method="post",code="400"} 3 1395066363000

# Escaping in label values:

msdos_file_access_time_seconds{path="C:\\DIR\\FILE.TXT",error="Cannot find file:\n\"FILE.TXT\""} 1.458255915e9

# Minimalistic line:

metric_without_timestamp_and_labels 12.47

# A weird metric from before the epoch:

something_weird{problem="division by zero"} +Inf -3982045

# A histogram, which has a pretty complex representation in the text format:

# HELP http_request_duration_seconds A histogram of the request duration.

# TYPE http_request_duration_seconds histogram

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="0.05"} 24054

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="0.1"} 33444

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="0.2"} 100392

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="0.5"} 129389

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="1"} 133988

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="+Inf"} 144320

http_request_duration_seconds_sum 53423

http_request_duration_seconds_count 144320

# Finally a summary, which has a complex representation, too:

# HELP rpc_duration_seconds A summary of the RPC duration in seconds.

# TYPE rpc_duration_seconds summary

rpc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.01"} 3102

rpc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.05"} 3272

rpc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.5"} 4773

rpc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.9"} 9001

rpc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.99"} 76656

rpc_duration_seconds_sum 1.7560473e+07

rpc_duration_seconds_count 2693

Each block has a number of distinct elements. Taking http_request_duration_seconds as an example:

-

# HELP http_request_duration_seconds [...]line documents a metric, -

# TYPE http_request_duration_seconds histogramdefines the type of metric, in this case a histogram - The next 5 lines describe individual bucket cutoff values as a label:

le="..."and their respective counts, -

http_request_duration_seconds_sum 53423is a sum of all observed values aggregated in this histogram, - Lastly,

http_request_duration_seconds_count 144320is the count of observed values.

Metrics labelling

Similarly to log contexts, metrics are usually annotated with labels, which contextualize metric values. Some metrics, such as CPU utilization, rarely require sophisticated labelling at an application level to be useful, while others are virtually useless without being broken up across at least one dimension with labels. A good example of such metric is HTTP request duration, which is informative only if collected for each HTTP endpoint separately.

As another analogy to log context, metrics labels can be added at various stages:

- When application is instrumented with metrics,

- When log collector gathers metrics from a particular application, host, Kubernetes pod, namespace etc, and labels them accordingly,

- When metrics server receives metrics from various metrics collectors responsible for various environments, or various parts of a system.

Metrics labels tend to be quite diverse compared to log context. Different metrics may require different approach to labelling:

- Histograms could almost universally leverage buckets or quantiles, which would make little sense in case of a CPU utilization gauge,

- Host level metrics such as free memory might benefit from different labels than K8s cluster level metrics, or application endpoint metrics; Nevertheless, some labels might sometimes prove useful in all three contexts,

- Some metrics and labels are highly specific - for instance, JVM metrics and JVM memory region labels are of little use outside of JVM applications.

Handling metrics cardinality

Unlike log context, which enhances log entries without increasing the number of log events, labelling often introduces dimensionality to otherwise scalar metrics. For each unique label value - or each unique combination of values in case of multiple labels - the metrics exporter exposes a separate metric value, which then needs to be collected and stored in metrics server in a separate time series. A measure of how many individual values are exposed by an individual component, or a system, is called cardinality.

As the system instrumentation grows in terms of number of collected metrics, instrumented components, label keys and possible label values, the number of time series that metrics server needs to handle also grows - and for each individual metrics, its cardinality can be as high as a product of its individual labels cardinalities across the instrumented system:

$ |S_{\text{metric}}| = \prod_{i=1}^{n} |S_{\text{i}}| = |S_1| \times |S_2| \times … \times |S_n| $

If we take a metric with 10 labels, each having only 2 possible values we get:

$ |S_{\text{metric}}| = \prod_{i=1}^{n} |S_{\text{i}}| = \prod_{i=1}^{10} 2 = 2^{10} = 1024 $

As you can see, the total cardinality of a metric can grow rapidly even when individual labels have very few possible values. For this reason, it is often highly impractical to enforce a large, common set of mandatory labels across large sets of individual metrics in a distributed system - beyond a limited number of basic, virtually universal labels. Common examples include labels describing:

- Application name or other identifier,

- Hostname and/or IP address,

- Kubernetes-related metadata - in case of systems deployed using it,

- Environment, if metrics from multiple environments are sent to a single metrics server.

This way, systems can be instrumented with less up-front cardinality. Moreover, it is often practical to revisit how metrics are actually used, and filter out unnecessary labels accordingly. This should help reduce the number of time series in a metric server, which usually improves performance and/or helps limit the cost in case of vendor-provided metrics servers.

Metrics utilization

There are two primary use cases that utilize metrics:

- Real-time metrics visualization on dashboards,

- Reports showing historical metrics data,

- Metrics-based alert rules.

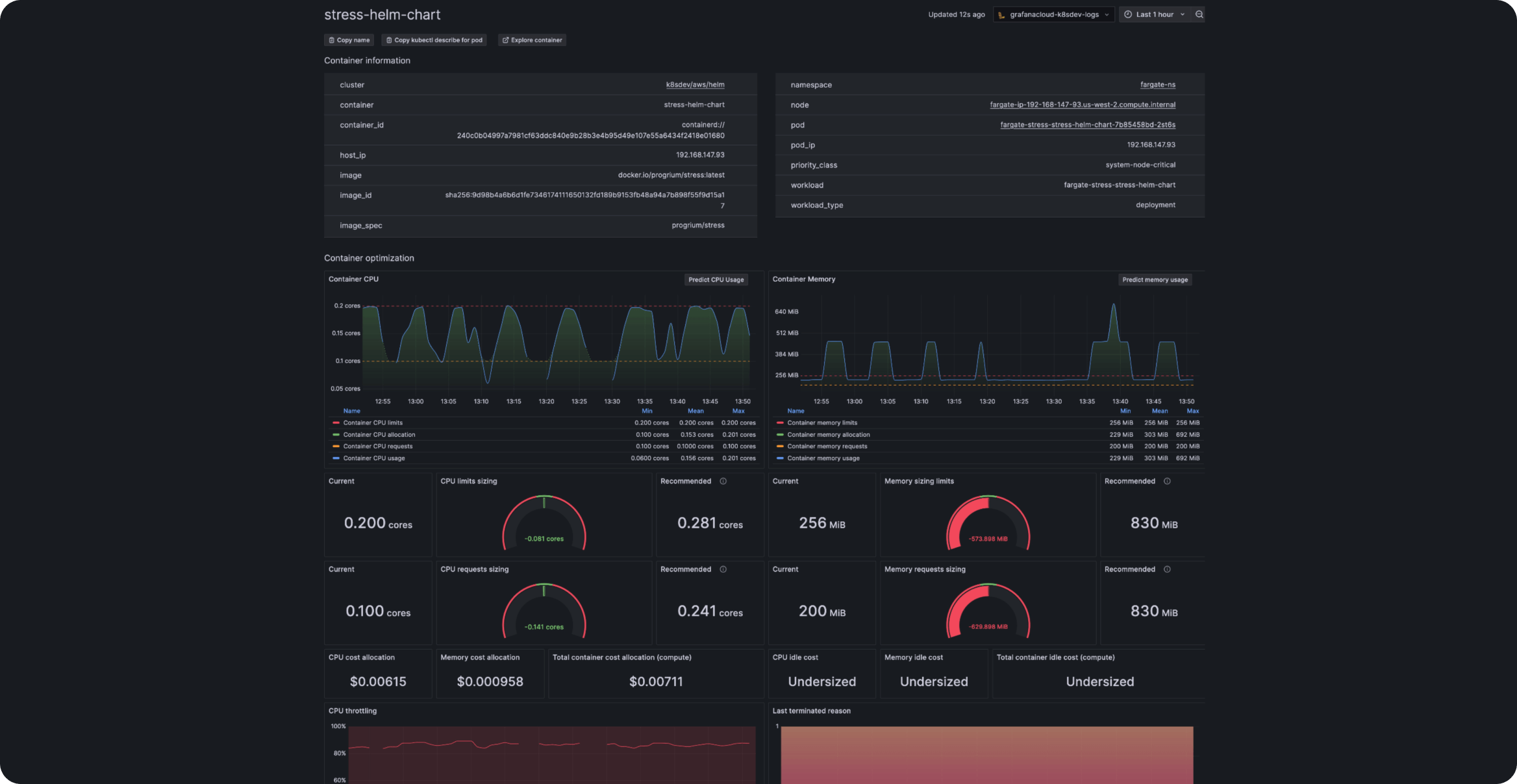

In case of dashboards and reports, metrics are typically shown in visual or tabular form - such as graphs, pie charts and gauges. An example Grafana Cloud dashboard for Kubernetes is a good example:

In case of alerting, a set of rules is set up against available metrics and check periodically if metrics meet a condition. When an alert rule is triggered, notification would be sent via a specified communication channel, such as:

- Email,

- Slack, Discord or other messaging app,

- Dedicated incident management solution, such as PagerDuty.

This makes metrics immensely useful for continuous and automated system monitoring, without human beings actively watching metrics to capture anomalies, such as:

- Unusual error rates,

- Hardware resources being exhausted,

- Increasing event processing lag,

- Breaching Service Level Objectives, e.g. p99 latency on a certain endpoint.

Similar measures can be taken by utilizing and processing logs, however this approach has several drawbacks:

- Logs often need substantial processing to yield insights easily accessible via metrics,

- With logs being highly flexible and often containing a lot of freeform text, alert rules based on metrics computed from logs can be prone to inconsistency of logs and changes in log contents.

Therefore, metrics are often the second stage of distributed system instrumentation efforts, improving system’s observability in areas where logging proves insufficient or tedious.

Traces

Traces are perhaps the least frequently used type of instrumentation among the three. In fact, I have personally seen traces being utilized at any scale, and only a handful of cases where the organization would genuinely invest in instrumenting their systems with distributed tracing.

Traces are signals that allow to track how operations are executed in the context of a particular invocation, and structure this execution as a tree of units of work - called spans. Each span in a trace corresponds to a certain stage of execution, such as:

- Outbound HTTP request,

- Database transaction,

- Filesystem access,

- Computing results.

In short, traces help provide context that is missed entirely by metrics - which do not meter individual invocations in principle - and which is often generally available in system logs, however cannot be easily obtained without complex, compute-intensive log processing.

What are traces useful for?

It is sometimes rather tedious to comb through system logs from multiple distributed system components, in order to find the reason why API requests are sometimes so slow, or at which point is the execution failing. In such cases, it is usually easier to retrieve traces related to this particular execution, and then analyze the span tree, looking for possible reasons.

Furthermore, since traces are emitted at a particular point in time, similarly to logs, and are by design correlated with a specific execution, it is natural to use them in conjunction with logs and metrics from the same time window, and relevant to this execution. Consider the following examples:

- Distributed traces show that a number of slow requests occurred, exceeding agreed SLOs by a considerable margin. The traces span tree indicates a particular database interaction is slowing down the request, and upon investigation of metrics of the database involved, evidence of CPU throttling is found.

- A number of traces is sampled for requests that failed with a bizarre error body. It is visible in these traces’ span trees that a certain request to an upstream service is failing consistently, and surrounding logs are investigated. The investigation shows the requests had been failing because the application’s keystore has some self-signed certificates besides the certificate issued by the organization and trusted by the upstream service.

How traces are collected?

Similarly to metrics, trace collection is handled by trace exporters and collectors. The exporter, such as OpenTelemetry, Zipkin or Jaeger, typically pushes the traces to the trace collector, which then aggregates traces from various sources and sends to a trace server:

Due to the aggregation step, the traces are often sent to the server with a certain delay, allowing to collect related trace information from possibly multiple exporters, until completion of a trace. This is often done by setting a certain timeout - if no new trace information, such as spans, are sent in for a set amount of time, the trace is closed and sent to the server.

Trace sampling

Unlike logs and metrics, which are usually ingested as whole, traces are frequently sampled down. There are several reasons for this approach:

- If every operation was traced, this would have produced tremendous amounts of tracing information, a case similar to excessive logging or excessive metrics cardinality,

- Most of the time, not all traces are truly needed. Some traces can be safely discarded without negative impact on traces usefulness,

- Traces are most useful when investigating undesired behaviors, and thus collecting all traces for the bulk of execution is impractical.

For these reasons, traces are typically sampled down to limit their volume, either by exporter or collector (or sometimes both). Since multiple sources may emit span information related to the same trace, ensuring they are sampled or rejected consistently requires either delegating the decision to trace collector - if there is only one - or passing down the information on sampling decision, such as sampled flag.

There are various approaches to trace sampling:

- Sampling a set percentage of traces,

- Sampling traces which meet specific criteria,

- Setting separate sampling policies for traces meeting various criteria.

It is not uncommon to prioritize certain traces when sampling. Most notably, traces related to failed and slow requests are typically found more useful than traces showing no anomalies, and may have significantly higher sampling percentages. Additionally, and important aspect is to maintain a consistent and sane approach to sampling - for instance, if we configure both exporter and collector to sample 1% of all traces, instead of desired 1% we would only get 0.01% of sampled traces.

Trace format

This simplified example from OpenTelemetry shows what span metadata might look like:

{

"name": "hello-greetings",

"context": {

"trace_id": "5b8aa5a2d2c872e8321cf37308d69df2",

"span_id": "5fb397be34d26b51"

},

"parent_id": "051581bf3cb55c13",

"start_time": "2022-04-29T18:52:58.114304Z",

"end_time": "2022-04-29T22:52:58.114561Z",

"attributes": {

"http.route": "some_route2"

},

"events": [

{

"name": "hey there!",

"timestamp": "2022-04-29T18:52:58.114561Z",

"attributes": {

"event_attributes": 1

}

},

{

"name": "bye now!",

"timestamp": "2022-04-29T18:52:58.114585Z",

"attributes": {

"event_attributes": 1

}

}

]

}

The most important properties of a span include:

- Span ID, trace ID and parent span ID,

- Timestamps for start and end time,

- Span name, providing a human-readable reference,

- Attributes, or labels bearing additional context, such as request URL, HTTP method, hostname etc.

After aggregation and sending to trace server, such as Grafana Tempo, traces can then be analyzed and visualized as shown in an example from documentation:

Summary

In this post, we have explored how the three basic building blocks of distributed system’s observability stack contribute to Engineering Teams’ ability to maintain and troubleshoot the system.

Logs are the most basic, and arguably critical part of application instrumentation, allowing to troubleshoot particular scenarios during incidents. As such, they are frequently first to be introduced in any system.

Metrics often come second after logs, and provide and ability to monitor the state of the distributed system and its infrastructure. Moreover, combined with alerting solutions they allow to continuously monitor a system and react when the first symptoms of an incident are visible.

Traces, on the other hand, are complementary to the first two, and are often implemented last if at all. The provide insights about particular executions that are not retrievable from metrics, while accessing them via logs is often tedious - assuming the logs actually have enough context to facilitate such search effort.